Gottfried Franz Kasparek

Declaration of love in dark times

On the Violin Concerto by Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari

With a conversation with Benjamin Schmid

Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari, born in Venice to a German painter and an Italian woman, was the prototype of the "German-Italian". He composed his operas in his mother's language and wrote most of his letters in his father's language. He lived in Munich for a long time and was completely out of time as a tone poet. He rarely paid tribute to verismo. At the center of his creative work were buffoopers, which continue the tradition in a highly artistic and original way. They are filled with the timeless magic of the great melody, combined with splendid comedy and the finest tonal colors. They all exist also in German versions authorized by him. "I quattro rusteghi"/ "Die vier Grobiane", "Le donne curiose"/ "Die neugierigen Frauen" and "Il Campiello" still appear again and again on playbills and are loved by audiences. But besides these, sacred works, lyrical chamber music and sensitive orchestral pieces would be discovered.

Wolf-Ferrari was indeed appointed director of the Mozarteum in Salzburg during the Nazi era, which he spent largely in Germany. However, he was not a Nazi, but a politically naive artist who retreated to the ivory tower. He wrote one of the most beautiful romantic violin concertos in the midst of the horror of World War 2, inspired by the deep affection of an old gentleman for a young woman. The very young violinist Guila Bustabo, an American who had stayed in Germany and had an Italian father and Czech mother, was the 67-year-old composer's last great love. She was a star at the time, a delicate and distinctive woman and an expressive musician. After the war she did not continue her career, but taught in Innsbruck and was an orchestral violinist in the USA. She died, almost forgotten, only in 2002 in Alabama. "Her" concerto lives and has found an ardent interpreter in Benjamin Schmid. Wolf-Ferrari drew motivically on works from his youth. The heavenly main theme of the first movement, for example, comes from the Liebesleid aria from an unfinished opera. A quotation from Franz Lehár's master operetta "The Merry Widow" - "There were two royal children..." - has to do with personal experiences of the unequal couple. Their love had to remain unfulfilled, like that of the king's children. Not everything in this concert is love poetry. In the final movement, which is actually lively, mystical passages come as a surprise, as if the Grim Reaper would drop by.

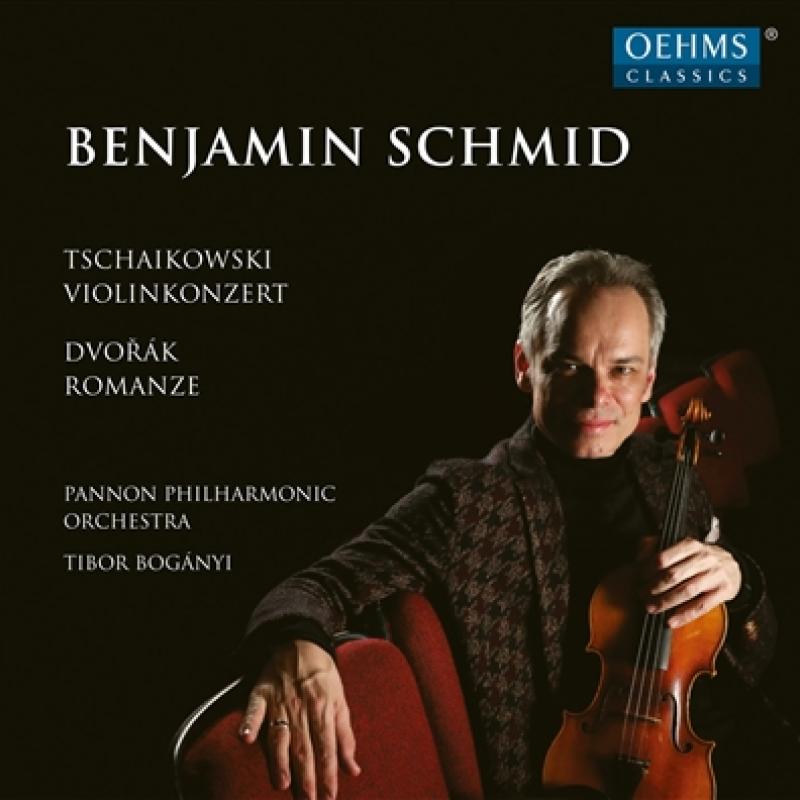

For Benjamin Schmid, "the form contributes significantly to the success and character of the concerto, it is ingenious!" The great violinist from Salzburg, who always analyzes the music he plays with direct emotion, finds "the first movement a shimmering melodious aria in the violin's dialogue with the flute, Wagnerian-baroque, operatic and episodic, still somewhat hazy in the orchestral treatment, but building up to three grand finales. A ravishingly beautiful F-sharp major song follows in the second movement, intimate, bright and substantial. The middle section in dark E-flat minor is a song in thirds that makes me think of Brahms and Schubert, with an artful return to the recapitulation in G major (!), then ingeniously modulating back down the semitone to the original F-sharp major, with the most tender, anxious question from the violas in the coda, answered positively after a long moment of silence, leading to the lyrical epilogue. The third movement is a recitativo, retrospective, highly dramatic, imaginative, threatening, celebratory, full of bursting virtuosity."

"In the fourth movement," Schmid continues, "a joyfully exuberant and virtuosic rondo theme appears, reminiscent of Beethoven's model, followed by a free virtuosic development for soloist and orchestra. But there are also mystical passages with poignant melodies. And then: one of the longest fully composed violin cadenzas at the end of the concerto, sounding out the lyrical spirit of the work once again. Even the orchestra, in Elgarian fashion, still interferes inconspicuously and in the most enchanting way with the fantasy, before a sweep to the shared, highly virtuosic conclusion."

The poetry of this music never becomes an end in itself; the virtuosity is always emotional expression. But, poignant as it is, is this not a troubling piece that denies the cruel reality of the time in which it was written? Love can be stronger than reality. And the clear maturity and intimacy of a music can also be understood as a counter-draft to the horror of its surroundings. As a vision of a better world. As a longing for a beauty that must not die.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)