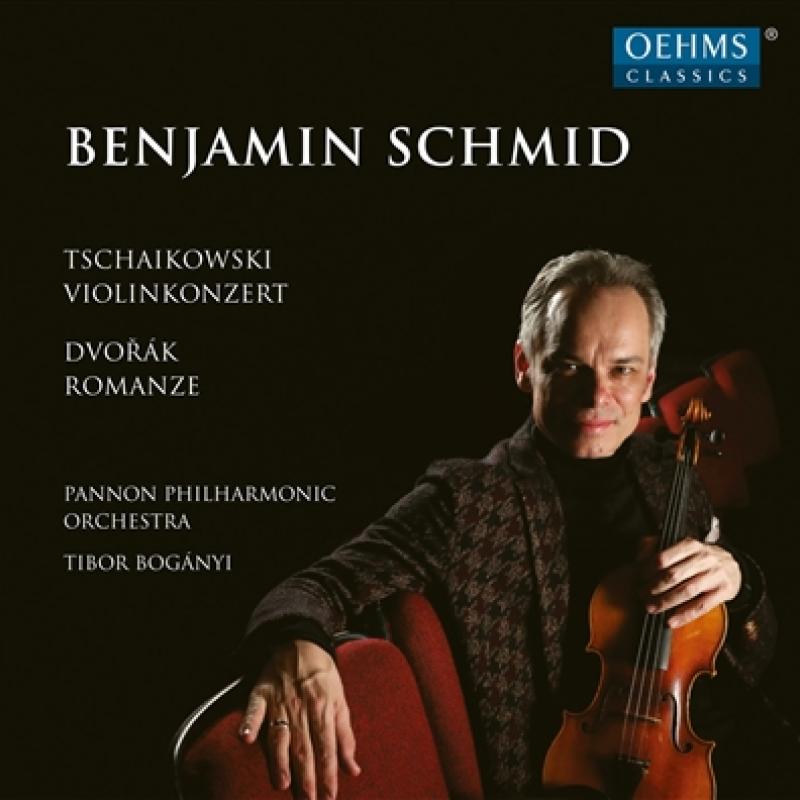

Benjamin Schmid (Violine), Pannon Philharmonic Orchestra, Ltg. Tibor Bogányi: Béla Bartók, Violinkonzerte Nr. 1 & 2, Gramola CD 99138; Tschaikowski, Violinkonzert D-Dur

Dvořák, Romanze für Violine und Streichorchester f-Moll, OEHMS CLASSICS CD OC 467

VIOLINKONZERT D-DUR OP. 35

ANTONÍN DVORÁK (1841–1904)

ROMANZE FÜR VIOLINE UND ORCHESTER F-MOLL OP. 11

Benjamin Schmid, Violine

Pannon Philharmonic Orchestra

Tibor Bogányi, Dirigent

Eduard Hanslick, der gefürchtete Kritiker seiner Zeit, fand anlässlich der Uraufführung von Tschaikowskis Violinkonzert nur wenig gnädige Worte: Es werde nicht mehr Violine gespielt, sondern „gezaust, gerupft, gebleut“. Den Siegeszug von Tschaikowskis einzigem Violinkonzert konnte er gottlob nicht aufhalten.

Antonín Dvorák komponierte seine zauberhafte Romanze für Violine und Orchester in f-Moll op. 11 irgendwann zwischen September 1873 und Anfang Dezember 1877. Das Werk erlebte seine Premiere am 9. Dezember 1877 in Prag. Gewidmet ist es dem tschechischen Geigenvirtuosen František Ondrícek, „seinem lieben Freunde“, selbst Komponist und einige Jahre später Solist der Uraufführung von Dvoráks Violinkonzert.

OehmsClassics freut sich, nach langer Zeit wieder eine CD mit Benjamin Schmid zu veröffentlichen, dem österreichischen Ausnahmegeiger. Schmid feiert in diesem Jahr seinen 50. Geburtstag – aus diesem Anlass wird das Label ein 20-CD-Set mit all seinen OehmsClassics- Aufnahmen herausbringen. Die Veröffentlichung ist für September geplant.

Liner Notes by Benjamin Schmid on his Tschaikowsky recording:

"… to fly as a soloist …"

Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto played an important role in my life as a violinist quite early on: I studied it with great youthful enthusiasm at age 14 and played it at the finale of the Concours International Yehudi Menuhin at age 17 with the Orchestre de Paris in the Salle Pleyel. Celebrated as the surprise of the competition, this 2nd prize (alongside two special prizes, categories Preclassics and Jazz) led to my first major orchestral engagements in Europe. Several years later this concerto was again my companion at several important successes at competitions. Three decades later I am still discovering new facets in the (again newly released) score. Iam interested in the classicistic dimension of a violin concerto, based on form, which uses a very compact orchestral apparatus; its drama is told much more through Tchaikovsky’s inimitably long, increasingly condensed developments than the many virtuoso violinistic stunts containedtherein. For this reason, the tempo I choose for the first movement’s lyrical secondary theme is not too slow – Tchaikovsky himself indicates only con molto espressione – so that the result will be in relation to the rest of the movement, being a tender but expressive side thought rather than an isolated, oozing island of feelings. Similarly, there is a movingly simple thematic idea that never appears again (!) when the orchestra begins. Tibor Bogányi, his orchestra and I do not prepare the solo violin’s ensuing entrance with a ritardando red carpet that Tchaikovsky did not notate; instead, the solo violin takes over part of a motif from the orchestra out of the blue, and only after a brief moment of reflexion creating from it a wondrous flower in the cadenza leading into the noble principal theme. Tchaikovsky’s instructions molto moderatissimo in the central section of the first movement and, in the third movement, the distinction between meno mosso (for the first subsidiary theme, cello fifths) and molto meno mosso (second subsidiary theme, oboe solo) seem to me to be important. In the present recording, made one day after two fiery concerts, we have doubtless interpreted the third movement’s vivacissimo quite distinctly – simply because with Tibor Bogányi and his magnificently flexible Pannon Philharmonic Orchestra, it is possible to fly as a soloist. Here I would also like to mention that my ruthless takeover of the tempo of the introductory solo cadenza in the third movement is more or less a soloist thrashing about; he has not yet noticed that the orchestra has left him alone. This is why, in his Rumpelstiltskin-like rage, it does not occur to him to play any prettily narrative rubati or ritardandi. Only in the last moment does he remember that here is where Tchaikovsky has written just the ritardando and the two fermatas. Mention must be made of the highly intimate sound of my wonderful Stradivari “ex Viotti, 1718” in the second movement, in which Ihave complied with Tchaikovsky’s instruction to use the mute (placed on the bridge of the instrument). The result is an utterly private sonic island in the midst of a highly expressive work.

Benjamin Schmid

March 2018